Since early this year, I have been fortunate to be involved in a research project on contemporary Japanese landscape architecture led by Assoc. Prof. Jillian Walliss and Dr Heike Rahmann. The project aims to capture the roles of contemporary Japanese landscape architects as change-makers who respond to the social, cultural and political climate in Japan through their practice, research and teaching.

Before the trip, my understanding of contemporary Japanese landscape architecture was shamefully limited; despite my interest in Japanese architecture and relationships with landscape, primarily cultivated by my identity as a Japanese, I had limited education on contemporary landscape architects and the impacts they are making in Japan and beyond. When spotlights are often on architecture or transitional Japanese landscape design and cultural practices, finding information regarding contemporary landscape architecture was itself a struggle. After being invited to the project and provided with a list of key interviewees, I better understood where to start researching. The Big Asian Book of Landscape Architecture also gave me a more thorough contextual background that I vaguely knew but never pondered about.

The three-week trip consisted of conducting interviews and filming four selected projects – Nihonbashi Garden (Tokyo), Queen’s Meadow Country House (Tono, Iwate), Okutama Therapy Trail (Okutama, Tokyo), and Hoshinoya Karuizawa (Karuizawa, Nagano).

We had the privilege of interviewing:

(though I couldn’t meet Tamotsu san personally due to the graduation ceremony)

Meeting and interviewing practitioners and academics who engage with landscape architecture encouraged me to reflect on how their design approaches and philosophy inform their unique design outcomes and teaching. Below are some of the ideas I took away from conversations with them.

No rush, waste nothing – Way of life & design approach reflected in the construction and maintenance of the place

At Queen’s Meadow Country House (QMCH), we worked on building a terrace together, involving: the cutting of trees, relocating young bamboo (seedling high) in root blocks, constructing a log structure, capping the gaps of the structure using bamboo root blocks, and filling and compacting the soil. Working on the terrace construction with Tase san was an eye-opening experience, both in terms of the process and attitude. I was particularly amazed that nothing was wasted. Tree branches were used to create a bird nest-like structure on the side, and young bamboo seedlings (with roots) were repurposed as part of the retaining wall, stabilising the soil. The terrace was constructed using materials available on the site, and the construction process utilised manual labour (no machines). Tase san repeatedly mentioned, “there is no need to rush” whenever participants (including myself) were trying to complete tasks quicker. The steady pace and celebrating the progress itself (rather than against a benchmark or goal) created a palpable sense of satisfaction and contentment among participants.

It is not only the project but also the process that reflects their design approach. In the interview, Tase san talked about the importance of sustaining peace of mind formed by a long-term vision and everyday routines for caring for the place. With a sense of responsibility to look after horses and the land, organisers at QMCH very much appeared to be visionary while living in the moment.

Also, they established a way to maintain the land with horses that considers the sustainability of a healthy lifestyle that benefits all parties – humans, horses and the land. It is through adjusting the site boundary for horses to roam and clearing plants at different times of the year, keeping horses out of the stable for most of the year except when horseflies are around. They realised that horses were happier outside, and the humans had less work to do as horses went out to feed themselves and cleared overgrown plants.

While the countryside landscape and prior knowledge about the project would have influenced our mindset, it is their modest and inclusive attitude with the willingness to share knowledge that is at the core of the QMCH. Visiting QMCH made me consider the role of a project in connecting and educating people on an ongoing basis, focusing on experiences the place and people can offer.

In a continuum of time and waterway – responding to the past, present and future

‘Responding to context’ is a phrase often overused in both architecture and landscape architecture (including among students). But talking with Japanese landscape architects revealed a more profound way of understanding the context, considering the past, present and future on a broader scale and in detail. Tase san mentioned Kazuo Saito’s perspective on situating a project in relation to the water system, from the spring in the upper stream (in)to the sea as a whole. For example, the decision not to use pesticides and herbicides for farming was for looking after animals, insects, crustacea, and plants, but also for farmers who wish to farm organically downstream. If the upper stream is polluted, it affects the entire waterway (all the way to the sea) and surroundings. Furthermore, Tase san hopes to see a better connection between the sea and the river in the future – restoring the salmon run and associated food chain. It was incredible to hear how the considerations of the broader context and other stakeholders inform their design decision-making.

Another example was the Nihonbashi Garden on the rooftop of the Mitsukoshi department store in Tokyo by Landscape Plus (Hiraga san). The vegetation forming the garden references those at Meiji Jingu Shrine, one of Japan’s iconic artificial self-sustaining forests. It virtually creates a green corridor for non-human organisms to expand their habitats. While rooftop gardens are a topical typology of urban green spaces, I found the ongoing care of the Nihonbashi Garden particularly interesting. Twice a year, the client receives a biodiversity report on the observed living creatures documented by professionals, revealing how the ecosystem on the rooftop has been growing over time. Furthermore, it was thrilling to hear that the rooftop landscape reflects and reminds of seasonal changes that local senior members would reminisce about the now-disappeared native landscape of Tokyo. Embracing the ever-changing nature of the garden makes this project responsive to the past and future.

Another aspect of marking and respecting the continuum of time is through distinguishing the present from the past. Katagi san told us about her project at Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto, which strict heritage protection required detailed consultations with archaeologists and historians. In order to help identify the time of stone construction, Katagi san mentioned that craftspeople would leave chisel marks for quarrying the stones as the types of chisels used can indicate the time. It was fascinating to imagine how people in the future would interpret the project completed in this period in relation to the past, and how we design now can be tectonically and materially true to the present.

What defines the quality of design

Some of the memorable stories from the trip were about how to produce quality design under a limited budget. For example, Okutama Therapy Trail by Studio On Site (Mitani san) highlighted the design and construction process that elevated the engineering solutions to the modest yet beautiful design outcome. The landscape architects referred to the standard construction details commonly utilised for building retaining walls using timber and stones as they helped reduce construction costs. Mitani san mentioned that those details were fairly rational and reasonable; he acknowledged how contractors construct first and then proposed ways to better respond to the site through design. On the site, they worked closely with contractors to communicate the design quality they sought – such as the neatness of finishes and the alignment of fixtures. By the end of the construction stage, Mitani san noticed that stone contractors neatly oriented the stones to match each other, alternating the ordered direction row by row. The way contractors responded to the project reveals how the control over design quality is not just about documentation but also the communication of design intent and the shared vision with those who build it. Moreover, the considerate handling of materials successfully infused the poetics of spatial experience in standard engineering-driven construction. Materials’ heightened tactility, scent and textures demonstrated that high design quality could be about being tectonically honest with the materials.

Landscape architecture not just a profession but a common language for rediscovering & reminding landscape

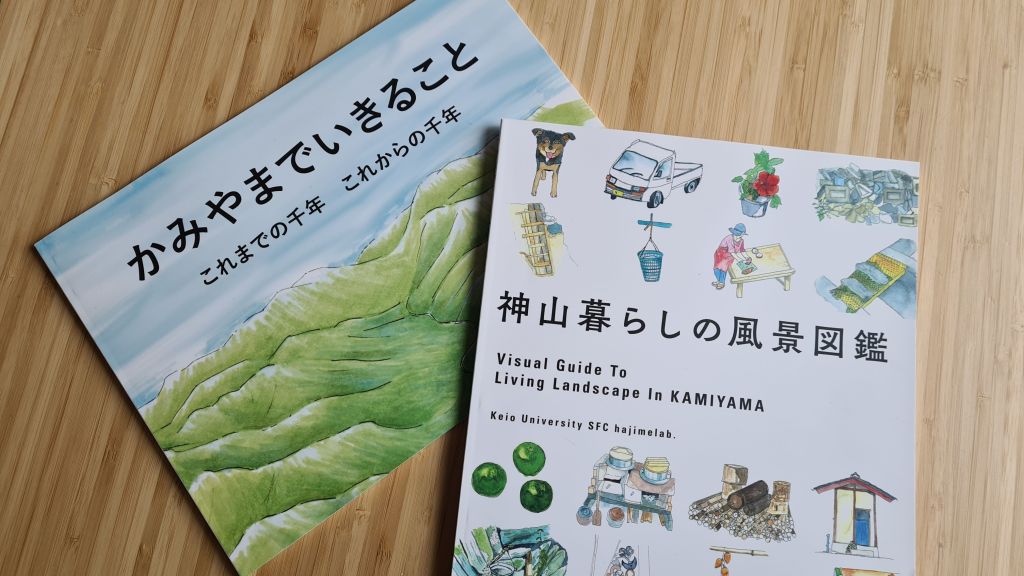

The definition of landscape architecture could be varied depending on who you ask – as a profession, a design discipline, an industry, etc. But Ishikawa sensei’s understanding of landscape architecture as a common language among built industry professionals and beyond made sense to me as a versatile, practical and mindful approach. Ishikawa sensei’s lab focuses on ‘rediscovering the landscape’ through fieldwork, mapping and community engagement, that ultimately becomes a tapestry of human activities, cultural practices and interactions with the place. For example, his lab’s work in Kamiyama town documented the cultural landscapes that led to the council developing the planning code for neighbourhood characteristics. He also mentioned that if a landscape architect has a seat at the table, they need to be able to remind the project team of the broader context and the flow of time that the project is responding to. At the same time, professionals in different fields also should have a shared understanding of the value of a landscape in order to move forward together. Therefore, while tertiary education in landscape architecture predominantly focuses on producing specialists (i.e. registered landscape architects), it would be beneficial for all built industry professionals and students to be educated in understanding the landscape and the importance of landscape architecture.

These ideas are only some fragments from the trip to Japan. There are lots more I wish I could write here, but I believe it’s best to hear from those interviewees themselves. I’m currently editing interview videos and putting together a website expected to finish in early 2022 – it will be available online soon. Stay tuned!