(Disclaimer: As I have not completed any formal education in neuroscience, please let me know if there is anything factually incorrect!)

Since I was a bachelor’s student, studying phenomenology in architecture has helped me understand the relationships between sensory experiences and architecture. While there are active discussions in design discourse on the elements of phenomena in the (built) environment – temperature, humidity, light and shadow, tactility, scent, visibility, etc., what connects phenomena to the subjective spatial experience of architecture, in other words, the state of being conscious of spatial qualities and own feelings, is something I had never thought about. My curiosity about consciousness from a neuroscientific point of view encouraged me to think about the concept of consciousness in the process of architectural experience.

Edmund Husserl, one of the founders of phenomenology, considers consciousness as an intentional activity by its nature. As phenomenology recognises that all experiences entail a temporal horizon, Husserl points out that consciousness “extends to capture past moments of experience and temporal objects” (Kelly n.d.). Similarly, in Martin Heidegger’s terms, consciousness of Reality is described as Being-in-the-world (note: it encompasses many meanings). For Dasein (“being-there“, meaning existence), Being-in-the-world is an essential characteristic understood as a “unitary phenomenon, as opposed to a contingent, additive, tripartite combination of Being, in-ness, and the world” (Wheeler 2011). The theme of consciousness or time-consciousness has played an essential role in the discourse of phenomenology from a philosophical point of view.

As a scaffold to consider a neuroscientific understanding of consciousness, this article bases ideas on Gerald M. Edelman’s Wider than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness, which explores the notion of consciousness from a biological point of view rather than a metaphysical perspective. Edelman questions: “How can the firing of neurons give rise to subjective sensations, thoughts, and emotions?” (Edelman 2005, xiii). However, I acknowledge that this field of study has various scientific research approaches that situate different propositions; this reference presents one way of thinking. Below is my attempt at summarising the key ideas behind the concept of consciousness relevant to one’s sensory experience.

In defining ‘consciousness’, this article refers to Edelman’s descriptions:

- Primary consciousness (sensory consciousness): “Primary consciousness is the state of being mentally aware of things in the world, of having mental images in the present” (Edelman 2005, 8-9).

- Higher-order consciousness: “the ability to be conscious of being conscious, allowing the recognition by a thinking subject of his or her own acts and affections” (Edelman 2005, 9).

- Both forms of consciousness require an internal ability to deal with tokens or symbols.

1. Consciousness is inherently subjective

Consciousness consists of the awareness of the moment and the remembered present shaped by personal past experiences and memories. The idea of “remembered present“ reflects that all the past experience is engaged in forming integrated awareness of a single moment (Edelman 2005, 8). Primary consciousness is established on subjectivity, incorporating one’s entire life experience. As consciousness is connected to one’s body, mind and the passage of time, Edelman argues that consciousness is a process and not a static thing: “The process of consciousness is a dynamic accomplishment of the distributed activities of populations of neurons in many different areas of the brain” (Edelman 2005, 6).

Gathering sensory inputs from an individual’s body forms part of ways to be conscious of something. In Conscious Experience, Fred Dretske states, “seeing, hearing, and smelling x are ways of being (perceptually) conscious of x – to see and feel a thing is to be (perceptually) conscious of it” (Dretske 1993). In addition, Dretske makes a distinction between thing-awareness and fact-awareness, where to be thing-aware of a difference is to be aware of the thing (objects, events, or condition) that makes the difference, whereas to be fact-aware of the difference is to be aware of the fact that there is a difference (Dretske 1993, 268). In spatial experience, one example might be a situation where one is aware of drops of water from the sky through feeling and seeing them (thing-aware, not necessarily knowing they are rain). On the other hand, one can become aware that it rained a while ago by seeing a past weather forecast without experiencing rain (fact-aware). This observation highlights the temporal factor in the formation of consciousness.

Memory plays a critical role in referencing past experiences in the formation of consciousness. Memory is the “capacity to repeat or suppress a specific mental or physical act” (Edelman 2005, 51). While different memory systems encompass diverse interactions between different parts of the brain, memory emerges due to changes in “synaptic efficacy (or synaptic strength, meaning the strength of communication between neurons) in circuits of neuronal groups”(Edelman 2005, 51). Such changes lead to an increase in similar circuits, yielding the repetition of similar output. (Edelman 2005, 51). However, no two experiences are identical; events of memory remain “dynamic and context-sensitive”(Edelman 2005, 52), which makes them associative. Scientists and philosophers agree that this subjectivity of the target phenomenon is the fundamental methodological problem in consciousness research (Edelman and Tononi 2000, 139).

2. A fundamental process in the brain shaping consciousness is categorisation

Cantwell describes categorisation as “the process of assigning unique responses to different groups of stimuli” (Cantwell et al. 2015, 1598). There seem to be different ways the brain recognises similarities and assigns categories, but here, I’d like to dive deep into perceptual and conceptual categorisation. In Edelman’s words, perceptual categorisation is the process of making sense of the world, allowing an individual to “carve up the world of signals coming from the body and the environment into sequences that result in adaptive behaviour” (Edelman 2005, 49). Perceptual categorisation processes the similarity of one thing to another and forms associations between stimuli and responses. On the other hand, conceptual categorisation re-describes perceptual information into conceptual ideas, focusing on what objects do. (Mandler 2000, 3) For example, conceptual categorisation allows an individual to distinguish a concept of a dog from a cat.

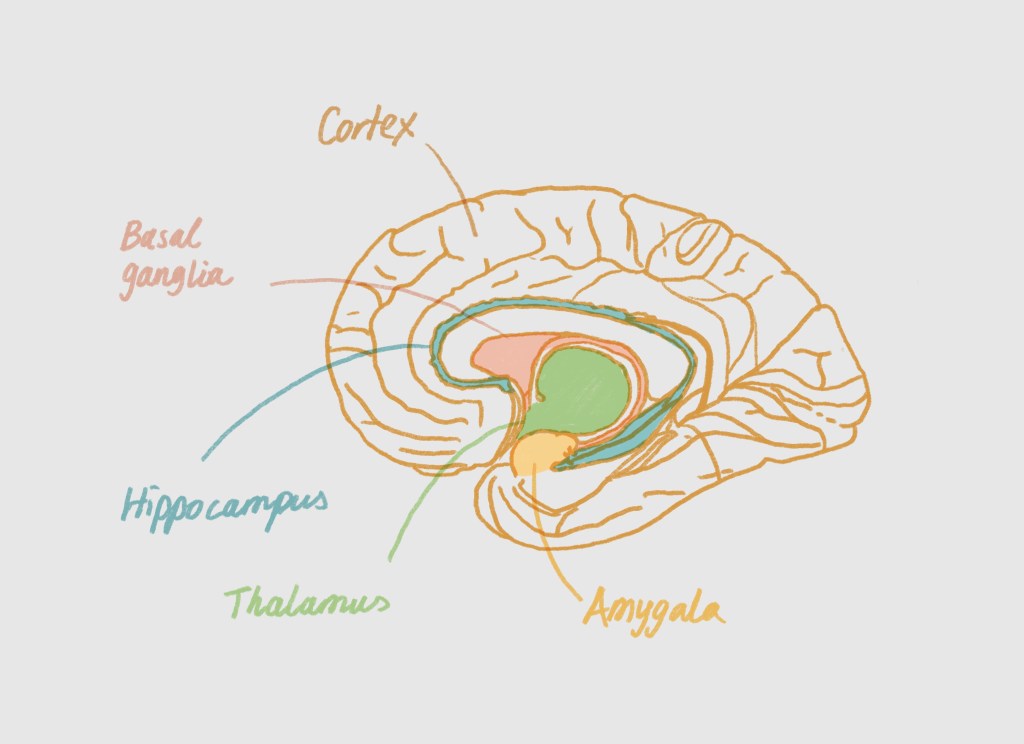

Before exploring how perceptual and conceptual categorisation work, I’d like to summarise what key brain components are and do in the process (apologies, it is a very dry summary):

- The cortex is subdivided into regions that mediate different sensory modalities, such as hearing, touch, and sight.

- Neuronal communication occurs by a combination of electrical and chemical events – neurons transmit an electrical potential (action potential). Different chemical structures in various brain regions create different effects, and their distribution and occurrence can significantly affect neural activity.

- Thalamus: essential for conscious function, receiving information from different sensory receptors (located in eyes, ears, skin, etc.) that serve different modalities, and having reciprocal connections with the cortex.

- Hippocampus: essential for memories of a sense of place. Removal of hippocampi leads to a loss of episodic memory (memory of specific episodes or experiences in life).

- Basal ganglia: relates to procedural memory (e.g. remembering how to ride a bicycle) and other non-conscious learned activity.

(The parts of the brain outlined above are by no means the only areas responsible for the functions listed – the assignment of functions to specific brain areas seems to be challenged in the rise of discourses around neuroplasticity.)

The neuronal interactions between sensory receptors, the subcortical system concerned with temporal succession (the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum), and the different areas of the cortex are important in shaping the categorisation process. However, there is intrinsic diversity in the process and outcomes of perceptual categorisation. Edelman writes: “Different individuals have different genetic influences, different epigenetic sequences, different bodily responses, and different histories in varying environments. The result is enormous variation at the levels of neuronal chemistry, network structure, synaptic strengths, temporal properties, memories, and motivational patterns governed by value systems. In the end, there are obvious differences from person to person in the contents and styles of their streams of consciousness” (Edelman 2005, 34). For example, even if every person touches the same object, they all have unique and plastic neural connections from the sense of touch in the hand through the thalamus to the region of the somatosensory cortex.

The categorisation relies on sampling signals from the world through sensory receptors, and attention can play a crucial role in the process. Koch and Tsuchiya argue that attention ‘selects’ information of current relevance to the organism, leaving the non-attended data neglected (2007, 16). Noting that the two tend to be conflated by scientists, they analyse selective attention and consciousness as two distinct brain processes that can occur independently. Since many research experiments in the study of consciousness and attention (at least those evaluated in Koch and Tsuchiya’s journal article) have a heavy focus on vision as the source of sensory information and often involve the perception of a single object in an otherwise empty display, the ways complex phenomenological conditions impact multi-sensory attention and human consciousness remains a question (if anyone knows a good article to read, please send it my way!).

3. A conscious moment is unitary yet distinctive

Considering how one’s body has countless sensory receptors, the way the mind brings all collected information together, processes them and allows conscious experience to emerge is fascinating. Edelman articulates that “Any experienced conscious moment simultaneously includes sensory input, consequences of motor activity, imagery, emotions, fleeting memories, bodily sensations, and a peripheral fringe. … one unitary scene flows and transforms itself into another complex but also unitary scene” (Edelman 2005, 61).

The idea of ‘integrated yet distinctive’ may resemble a film, where each frame contains different colours, shapes, characters, lighting, sets and backdrops. However, when the frames are seen in a sequence, they collectively tell a story, shaping one’s experience. While multiple cortical regions are functionally segregated for different elements shown on each frame, there is no superordinate area bringing all types of perceived elements together into a coherent percept. What enables the spatiotemporal coordination across multiple networks of the brain is reentry. According to Edelman and Gally, reentry is the “ongoing bidirectional exchange of signals along reciprocal axonal fibres linking two or more brain areas” (2013, 1). By synchronising and integrating neural activity patterns across functionally segregated cortical areas, the reentry process brings together cross-modal sensory characteristics. It highlights the significance of communication across different brain areas in understanding the multi-sensory experience.

Additionally, the ability to distinguish one from the whole and link specific sensory information to a particular response demonstrates the power of consciousness in phenomenological experience. Edelman describes: “being conscious means one can differentiate one ‘quale (a quality or property as perceived or experienced by a person)’ out of multidimensional qualities such as sensory input, consequences of motor activity, imagery, emotions, fleeting memories, bodily sensations, and a peripheral fringe. This distinction can be made by dynamic core, a functional cluster with numerous dynamic reentry interactions, mainly in the thalamocortical system. (a complex system that can maintain functionally segregated parts while integrating the activity of parts over time)” (Edelman 2005). There may be some crossovers between dynamic core, selective attention, and conceptual categorisation in terms of identifying specific sensory information from diverse pieces of sensory information and making neural associations with conceptual understanding.

Conclusion

The deep dive into the intersection of phenomenology, neuroscience and architecture reveals the consistent emphasis on the subjectivity of spatial experience, highlighting how one’s physical, physiological, neural and cognitive conditions, as much as the exposure to environmental, social, cultural and educational contexts, influence how one perceives and feels the world. It was exciting to learn that the interactions, communication and coordination across various areas within and beyond the brain (the body as a whole) enable the shaping of the sensory experience. As perceptual categorisation and conceptual categorisation, along with the memory system, develop on finding associations between elements in present and past, the discourse leads to the significance of exposing oneself to diverse experiences, environments, multi-sensory elements (both physical and phenomenological) and ways of thinking, in order to develop the ability to identify, acknowledge and appreciate spatial and architectural experiences that one otherwise cannot.

Bibliography:

Aydede, Murat, and Güven Güzeldere. 2005. ‘Cognitive Architecture, Concepts, and Introspection: An Information‐Theoretic Solution to the Problem of Phenomenal Consciousness’. Noûs 39 (2): 197–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0029-4624.2005.00500.x.

Cantwell, George, Matthew J. Crossley, and F. Gregory Ashby. 2015. ‘Multiple Stages of Learning in Perceptual Categorization: Evidence and Neurocomputational Theory’. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22 (6): 1598–1613. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0827-2.

Dretske, Fred. 1993. ‘Conscious Experience’. Mind 102 (406): 263–83.

Edelman, Gerald M. 2005. Wider than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness. Nota Bene ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Edelman, Gerald M., and Joseph A. Gally. 2013. ‘Reentry: A Key Mechanism for Integration of Brain Function’. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00063.

Edelman, Gerald M., and Giulio Tononi. 2000. ‘Reentry and the Dynamic Core: Neural Correlates of Conscious Experience’. In Neural Correlates of Consciousness, edited by Thomas Metzinger, 139–52. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/4928.003.0012.

Heidegger, Martin, John Macquarrie, and Edward Robinson. 2007. Being and Time. Malden (Mass.): Blackwell publ.

Kelly, Michael R. n.d. ‘Phenomenology and Time-Consciousness’. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (blog). Accessed 29 November 2024. https://iep.utm.edu/phe-time/.

Koch, Christof, and Naotsugu Tsuchiya. 2007. ‘Attention and Consciousness: Two Distinct Brain Processes’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11 (1): 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.10.012.

Mandler, Jean M. 2000. ‘Perceptual and Conceptual Processes in Infancy’. Journal of Cognition and Development 1 (1): 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327647JCD0101N_2.

Wheeler, Michael. 2020. ‘Martin Heidegger’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Fall 2020. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/heidegger/.