A recent weekend visit to Alowyn Gardens in Yarra Valley, known for all-season thematic ornamental gardens and a nursery, made me think more about what makes a garden special. Over the last 27 years, Prue and John transformed the character of the seven-acre land that used to be a neglected trotting farm. They developed the master plan of the garden based on the local conditions, progressively creating beautiful experiential gardens and experimenting with their designs, including planting. Different zones of gardens seemed to be based on varying degrees of ongoing human interventions, let alone the design processes. From the landscape architecture perspective, learning about Alowyn Gardens encouraged me to think about design thinking behind the garden design.

Going back to the meaning of ‘garden’

While the name ‘garden’ suggests the linkage to the typology of gardens, defining it as one of spatial typologies appears to undermine its unique characteristics and relationships to humans. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word garden has the Proto-Indo-European root gher-, meaning “to grasp, enclose”. The idea of enclosed external space (or simply external space with a defined boundary) suggests a level of physical separation from the world beyond, and the extent of space with greater potential for intimate human control.

This concept of intimate human control may give gardens a distinctive identity compared to other means of landscape interventions. A Dutch poet, Gerrit Komrij, considered gardening as an act of creating familiarity and bringing ideal close to home: “The essence of nature has never changed. We have merely ascribed to it different meanings, tamed it through a succession of visions. By imposing geometric order or through miniaturisation, we made it appear familiar to us so that, thus constrained, it corresponded to our nature or an ideal thereof. The symbolic value we conferred upon it, enabled us to avoid feeling ‘abandoned’ by nature or to view it as an ‘alien’ threat. As gardeners, artists and ritual worshippers, we have intervened in and elevated nature.” (p.13, from a lecture On the Necessity of Gardening, quoted in On the Necessity of Gardening: An ABC of Art, Botany and Cultivation).

Balancing the extent of control and the natural temporal evolution of the place is a factor for design thinking that may also be applicable in architecture, but particularly crucial in garden design since the most common design elements in gardens are living and ever-changing. After the visit, I decided to read more about different garden projects, and came to the conclusion that the way designers/gardeners attempt to control gardens reflects how they perceive and relate to the place more than anything; the overview for Garden Futures: Designing with Nature resonated with me: “Wherever people stake out a piece of nature to create a garden, its layout and design reveal much about how they relate to nature, be it as individuals or as a society… Every garden bears the marks of social and historical developments, political and commercial interests, and cultural value systems.”

Below are some thoughts on the readings that offered me different ways of thinking about gardens.

»You have to make big mistakes to create a garden.« – Interview with Piet Oudolf

Piet Oudolf is a notable Dutch garden designer whose drawings reveal his love of perennial plants curated in a ‘naturalistic’ manner (Prairie planting/a “matrix” style). In the interview for the Vitra Design Museum exhibition, Oudolf highlights the beauty of plants for their life cycle and not simply of flowers, responding to the interviewer whose question reflected interest solely in shapes, sculptural qualities and colour of flowers: “When you’re creating a garden, the question isn’t so much what a specific plant looks like when it’s in bloom, it’s more about how it interacts with all the other plants, whether they form a community. A flowering plant is only the second step, not the first, when you’re composing a garden…You have to look at the qualities of plants throughout the year. A plant that blooms early can still look wonderful in November because it has an attractive skeleton.”

This interview was an intriguing read, as the interviewer’s point of view echoed how gardens are often portrayed and ‘sold’ in the media: the collection of flowers in bloom, being naturally ‘instagramable’ and at its most visually ‘attractive’ state. On the other hand, Oudolf’s design thinking goes so much more profound, considering the relationships between diverse plants in temporality, finding joy in how the garden changes over time. Gardening as a process of observing and learning how plants behave must be crucial for acquiring design thinking and controlling what can be controlled.

How the High Line Gardeners Keep It Wild

After reading about Piet Oudolf, a question emerged: “How is Oudolf’s garden looked after?”.

‘Maintenance’ (or ‘to maintain’) is somewhat paradoxical when discussing gardens’ ever-changing nature. The word has etymological origins in “hold in hand” and “preserve from capture or loss”, implying the wish to keep the idealised image of a garden and the fear of losing control over it.

On another of Oudolf’s projects, the High Line in New York, Horticulturalist Andi Pettis writes about the role of gardeners who look after the design: “Over the last five years, the work of the High Line gardeners has been to facilitate and enhance the natural processes of growth, change, and movement in the landscape, and at the same time maintain the integrity of the original design by Oudolf and James Corner Field Operations”. Gardeners are “editors” who understand the design intent and check the proportion and balance between plants with varying sensitivities. Furthermore, species traditionally known as weeds that voluntarily grow, such as Milkweeds, may be kept and let grow (“[gardeners] have only to keep [invasive species] from becoming too wild”). This approach for human interventions in evolving gardens must have been one of the key considerations in the original design ideation, seeing the care needed for the garden’s life as an integral part of the design and ensuring the shared vision and design thinking holistically.

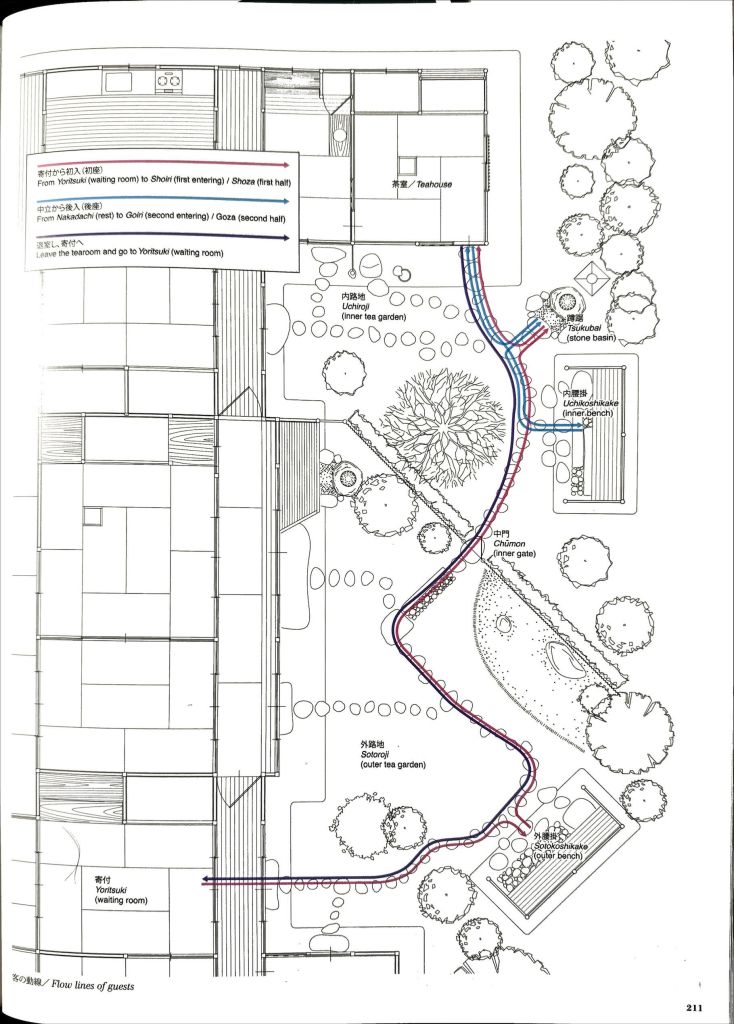

Garden as a device for human interactions – Japanese Tea House Gardens

Regardless of the scale, gardens are often designed to invite specific human behaviours and interactions with places and experiences. In such cases, factors such as human movements (speed, points for pause and actions, passage, etc.) impose design constraints on garden designs. A type of garden that must meet highly detailed spatial and experiential requirements may be the garden of a Japanese tea house. The book 33 Japanese Teahouses: From Rikyu and Enshu to Modern Times by Architecture and Urbanism includes pages describing the Etiquette of a Tea Ceremony using Kodokan roji (Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto) as an example, drawing out the circulation paths of guests from the waiting room to the tea house, out to the garden during the interval, and the return to the waiting room from the tea house after the ceremony. Plants, stones, built elements (such as fences, a stone basin and benches) and ground conditions are infused with meanings respectively and collectively. The garden becomes more of a composition of elements where spatial relationships between them are meticulously controlled by design, but not necessarily the forms of plants per se. Although the formality of the tea ceremonies adds a layer to the way elements are curated, their textures, forms, and materiality are embraced in a way that celebrates temporality and graceful aging, relating deeply to the spirit of tea ceremonies. It reflects the cultural practices and philosophical attitudes towards gardens unique to the history of Japanese tea house designs.

Thinking about garden design as an act of mediation between humans and nature, particularly the continuously evolving elements, made me ponder the impacts of design thinking and control over a timeframe way longer than typical architectural projects. Instead of the ‘practical completion’ (or the beginning of the human occupation) being the end of a project and the beginning of decay, garden design is an ongoing process that continues to evolve. Ongoing human control, in other words, how one responds to the state of the garden, tells more about humans themselves than the garden, and that I think makes gardens very special.

“It is not the visual element of the design that is important, but rather the location where objects and plants stand, the power they possess, and the way in which the space wants to function as a magical order.”

Erik A. de Jong. On the Necessity of Gardening: An ABC of Art, Botany and Cultivation

Reference and other related books:

A+U Publishing Co. 2022. 33 Japanese Teahouses: From Rikyū and Enshū to Modern Times. Kenchiku-to-Toshi Bessatsu = Special Issue, 2022,11. Tokyo: Shinkenchiku-Sha.

Cluitmans, Laurie, Maria Barnas, Jonny Bruce, Laurie Cluitmans, Thiëmo Heilbron, Liesbeth M. Helmus, Erik de Jong, et al. 2021. On the Necessity of Gardening: An ABC of Art, Botany and Cultivation. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Fumikita, Nishizawa. 1997. Architecture and Gardens: Collection of Survey Drawings by Fumikita Nishizawa. Tokyo: Kenchiku Shiryo Kenkyusha.

Harper, Douglas. 2001a. ‘Garden (n.)’. In Etymology of Garden by Etymonline. https://www.etymonline.com/word/garden.

———. 2001b. ‘Maintain (v.)’. In Etymology of Garden by Etymonline. https://www.etymonline.com/word/maintain.

Oudolf, Piet, and Noël Kingsbury. 2011. Landscapes in Landscapes. London: Thames & Hudson.

Pettis, Andi. 2014. ‘How the High Line Gardeners Keep It Wild’. The High Line. 10 June 2014. https://www.thehighline.org/blog/2014/06/10/how-the-high-line-gardeners-keep-it-wild/.

Vitra Design Museum. n.d.-a. ‘Garden Futures: Designing with Nature’. Vitra Design Museum. Accessed 29 October 2024. https://www.design-museum.de/en/exhibitions/detailpages/garden-futures.html.

———. n.d.-b. ‘Interview with Piet Oudolf’. Vitra Design Museum. Accessed 29 October 2024. https://www.design-museum.de/en/ueber-design/interviews/detailseiten/interview-with-piet-oudolf.html.

Yoshiki, Toda, and Nomura Kanji. 2021. 日本庭園を読み解く ~空間構成とコンセプト~. Marumo Publishing Co. https://www.marumo-p.co.jp/SHOP/B050.html.