In conjunction with the John Andrews exhibition at the MSD, a panel discussion event on modern heritage was held on 20 August, presented by MSD and Docomomo Australia. Four panels – Paul Walker, Philip Goad, Ruth Redden and Hannah Lewi – explored how modernist architecture, especially typologies such as social housing, industrial sites and infrastructural projects, have not received heritage recognition in society as much as older projects or public or single residential architecture.

After the event, I was left with a question – how early can the heritage values of a built fabric be recognised? While the passage of time and graceful aging must be critical factors that help yield a perspective on its heritage significance and enable a thorough evaluation, I wondered what the process of a building becoming a heritage site is like for modern architecture.

A few years ago, while studying cultural heritage, I began to explore what heritage means and how to understand it in relation to the Burra Charter. This article is partly a revisit to what heritage significance consists of but also a dive into what heritage means in different contexts, especially for elements of more recently completed built environments.

(For this article, I’m focusing on individual tangible heritage inhabitable places designed and built by humans, particularly in the 20th century and onwards; the definition of ‘heritage’ as a definition includes intangible heritage (language and traditions), objects and natural landscapes.)

Subjectivity and ‘Justification’ of Heritage Significance

A quick check of the Victorian Heritage Register Criteria and Threshold Guidelines gave me a measure of time for ‘heritage’ to be recognised:

Heritage is something from the past that we value in the present to such an extent we wish to preserve it in the future. As a general principle, a generation (or approximately 25–30 years) of use and interaction should pass before a place or object is considered ‘heritage’. The passage of time allows the cultural heritage values of a place or object to be more fully documented, consolidated and better appraised.

Furthermore, the Victorian Government Planning Practice Note mentions that from a planning perspective, the application of the Heritage Overlay is based on whether a potential heritage place has ‘something’ to be managed or not (p.2). The passage of time may also relate to the call for physical and material protection warranted by the registration as a heritage site. After all, the heritage register conserves the heritage significance that could otherwise be destroyed, removed or neglected.

This 25- to 30-year period aligns with the fact that Federation Square, the state heritage building on the Victorian Heritage Register built most recently, was completed in 1998 (26 years ago). But can this earliest recognition of heritage timeframe be considered applicable to any place for all levels of significance?

What becomes interesting is that the required degree of heritage significance, despite the almost consistent criteria across various heritage registration bodies, differs for different levels of protection. The Victorian Heritage Register’s guideline defines the significance threshold as:

The minimum level of cultural heritage significance that a place or object must possess to justify its inclusion on the relevant local, state, national or world heritage list.

Here, the verb ‘to justify‘ suggests something other than the nature of the building itself; the passage of time may not simply be for the heritage values to become apparent, but more importantly, the evidence of the heritage values to be formalised. For example, for a place to be added to the national heritage list, its heritage impacts on the country broadly need to be demonstrated, which could take a longer time to be appropriately documented compared to a place of local significance. Having said that, searching through locally significant places suggested that individually significant sites included in local heritage overlays seem not necessarily be more recently built than state-registered sites; it’s interesting to imagine whether, in reality, it’s easier to collate evidence for a new state heritage site than a less known local heritage site with limited documentation.

Protected by Planning Overlay but no significance acknowledged?

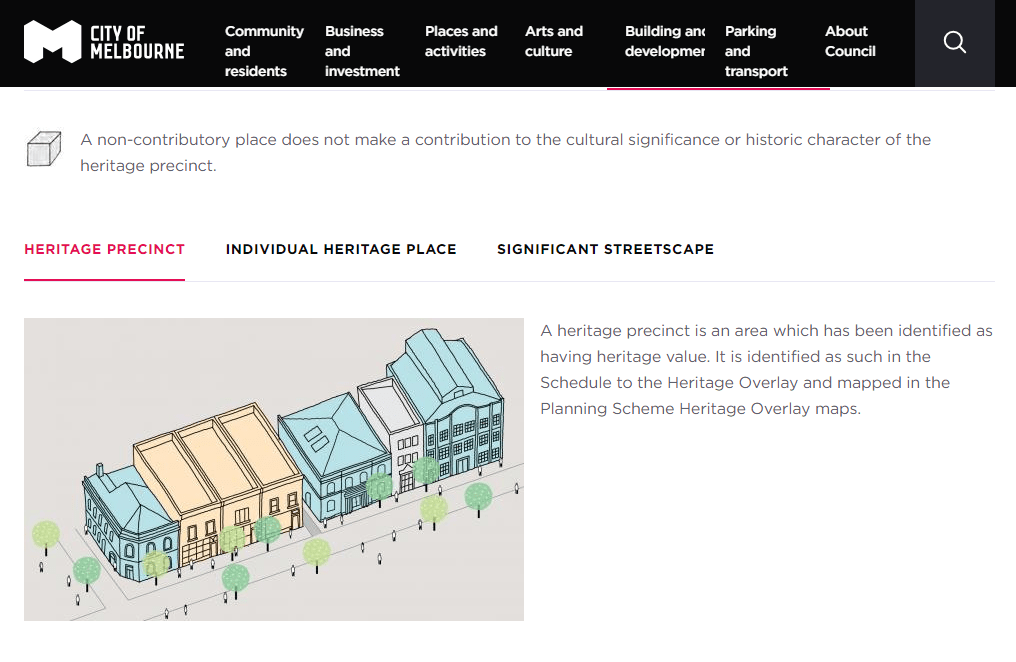

As I continued exploring sites of local heritage significance, I found the heritage grading that distinguishes different levels of heritage contribution interesting. In particular, the grade ‘Not contributory’ given to buildings within heritage precincts but without contribution to heritage significance is fascinating:

The building or place is not individually significant and not contributory within the heritage place. This is the lowest grading. Buildings with this grading were not typically constructed in the primary or secondary development periods of the area, or are a poor expression of that era.

They are included within a heritage overlay because any development of them may impact on the heritage significance of the precinct or individually significant or contributory places in the precinct.

(from City of Yarra – Heritage Overlay webpage. Similar definitions available on City of Melbourne Heritage Significance webpage)

In this case, buildings are protected not because they should be protected but because any developments would affect the heritage of their precincts. From the viewpoint of protecting modern projects, I wonder whether or not the concept of a precinct with heritage values could be a double-edged sword. At the same time, the protection may be beneficial for a more recently completed project, and the significance of a heritage precinct forms a framework for it to be perceived among older buildings with established heritage references. Can it ever be recognised as an individually significant heritage site in the future if its heritage values don’t perfectly align with the overarching heritage of the precinct?

Conclusion – more questions than clarity

The role of heritage registration as a way to protect something the public wants to keep for the future is crucial, especially in a time of constant scrap-and-build attitude in capitalist society. While the justification of the heritage values through a comprehensive collection of evidence is vital in ensuring that the site deserves public heritage protection, the acknowledgement of heritage through the documentation by its nature demands the time for the documentable heritage information to emerge. It is interesting to look further into how adaptive reuse and any renovation and extension affect heritage values in different settings, especially in modern architecture, which may still be fit for use compared to older built fabric. After all, heritage recognition that reflects public interest and attachment to the place gives so much meaning to the place’s future, and it’s a responsibility each of us has to bring places to public attention for protection.

Reference: Criteria for Assessment

At the state government level, the Victorian Heritage Act 2017 protects and registers heritage places and objects that are of significance to Victoria. Criteria for Assessment set by the Heritage Council of Victoria are used to evaluate whether a place or object is to be included in the Victorian Heritage Register. Slightly different criteria are included in the Victorian Government Planning Practice Note as recognised heritage criteria (added as italic texts):

Criterion A: Importance to the course, or pattern, of our cultural or natural history (historical significance)

Criterion B: Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of our cultural or natural history (rarity)

Criterion C: Potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of our cultural or natural history (research potential)

Criterion D: Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places or objects or environments (representativeness)

Criterion E: Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics (aesthetic significance)

Criterion F: Importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period (technical significance)

Criterion G: Strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons. This includes the significance of a place to Indigenous peoples as part of their continuing and developing cultural traditions (social significance)

Criterion H: Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in our history (associative significance)