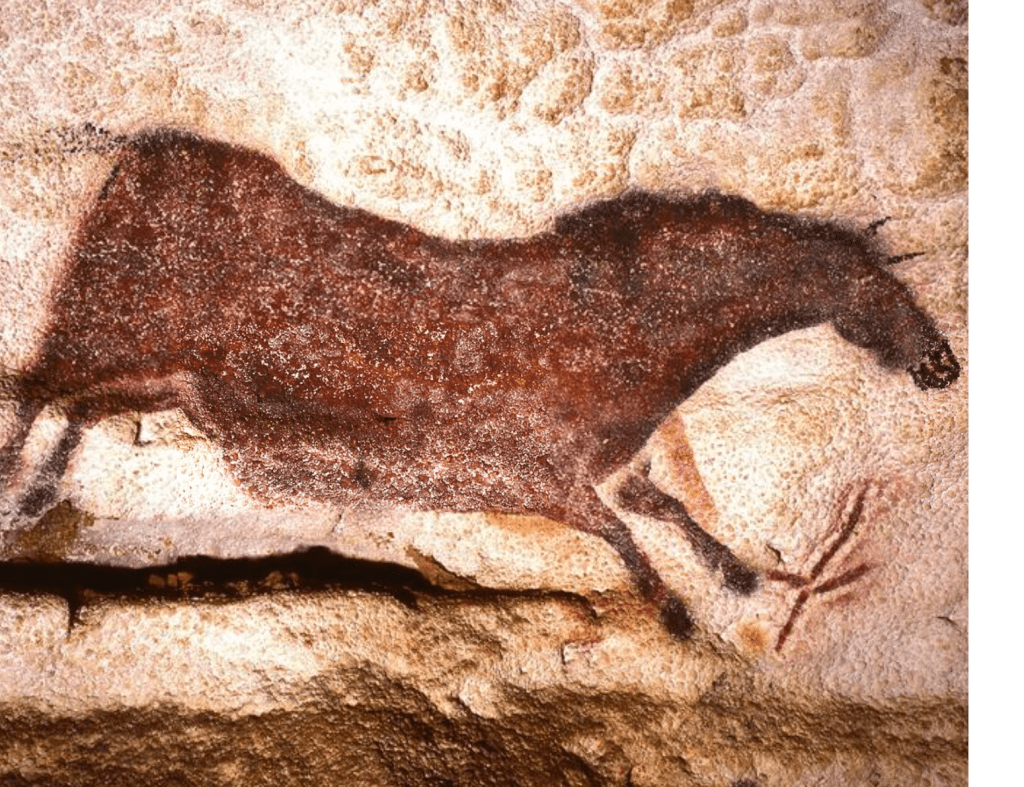

A few weeks ago, my mum sent me a parcel containing a book my auntie wanted me to have a read: La Chapelle des Pommiers (林檎の礼拝堂) by Kyoji Takubo, documenting the restoration/revitalisation process of Saint Vigor de Mieux in Falaise, France. While the writing capturing the challenges and reflection throughout the design process is fascinating, what made me pause and contemplate was a chapter on his visit to La Grottes de Lascaux. Takubo describes wall paintings of animals in the cave as “どうしようもないほど素直 (hopelessly pure/honest)”, where every aspect of the artistic expression “cannot be any more genuine than it”, creating a world of timeless freshness.

The word ‘素直’ in this context implies a combination of honest, authentic and pure attitudes that one might associate with a sense of innocence. Works from 21,000 years ago can still mesmerise people as something temporal, vivid and lively – such thought and the author’s interpretation of the works captivated me. At the same time, I wondered what makes us feel something is honest and genuine in the context of architecture.

Architecture, by its nature, is multifaceted in that it exists in ever-changing places for countless individuals with various ways of seeing, crafted by people with diverse design responses. The above example is only one person’s (Takubo’s) perception of La Grottes de Lascaux at a particular moment in time. Still, such a perception certainly resonates with someone like me on the other side of the world who hasn’t even been there.

I could have simply written about dissecting the meaning of architectural honesty in terms of built fabric, such as material and structural honesty (being true to materials and structure) and responding to contexts. However, this approach felt like neglecting all the other aspects of architectural practice that often hinder architects from maintaining an honest attitude; if architects think they cannot be honest, can architecture remain honest?

In the case above, it was also Takubo’s open-minded attitude to understand the sincere and genuine expressions of the painters of La Grottes de Lascaux that yielded such a poetic and beautiful interpretation. If that applies to architecture, then it must be the synergy of both architects’ and occupiers’ understanding of the place that achieves a mutual perception of honesty. In this writing, I will focus on those two standpoints towards architecture.

Architects’ mindset

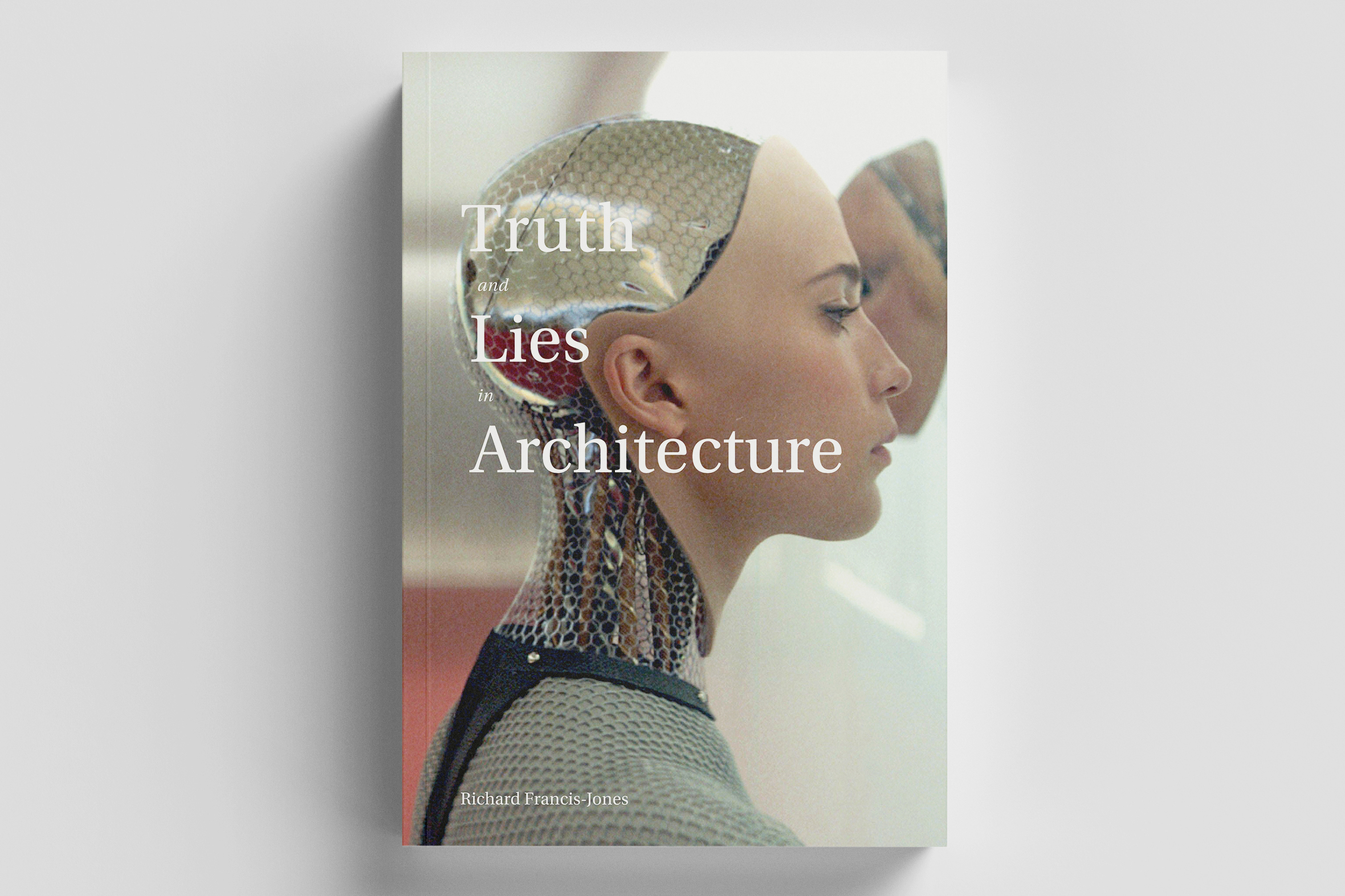

While researching honesty in architecture, I encountered Richard Francis-Jones’s book Truth and Lies in Architecture. Acknowledging the complexity of the world and the ongoing struggles architects face, Francis-Jones highlights two types of architects’ responses:

“Our professional culture and the natural human bias seem to result in two different responses from the architect. A kind of reactionary embrace, characterised by an overconfident and righteous self-belief, empowered through an opposition or competing negativity and intensified in the wake of success. Or a deeper realisation and understanding, perhaps intuitive, of the nature of the task, its complexity and vastness in relation to our trivial self-reference, that engenders a profound sense of melancholy.” (p.30)

The definition of melancholy may encompass negative connotations, but Francis-Jones clarifies it that “melancholy… is a state of recognition and acknowledgement of the human struggle with the way of the world or more accurately, our way with the world.” (p.30), suggesting that honesty in architecture comes from accepting as is the reality of the world in which we operate. The two categories mentioned above could be understood as a transition from one to another, where the more one realises the palimpsest of complex hurdles, the more melancholy and reflective one becomes.

As Francis-Jones claims “the melancholy of the architect may be the only true and authentic ‘place’ from which we can begin to work within the vexed conditions of contemporary life” (p.32), the state of melancholy may be where architects have a deep understanding of the place and contexts (hence the starting point). In this sense, honesty and genuine architecture may stem from knowing and being open to communicating the constraints and limitations of architecture.

People’s mindset

As Kenneth Frampton highlights in the Forward of Truth and Lies in Architecture the profession “has oscillated between masquerading as a metier akin to applied science or at another moment as a language or yet again as an abstract culture similar to music or eventually as little more than ‘a decorated shed'”, architecture is portrayed as having a myriad of values and meanings, often for the advantage of built industry practitioners who, in operating architectural practices, frequently need to demonstrate their relevance to the society where architecture has seemingly become part of commodified, consumable entities. But how can we promote and convince people of the value of architecture when architects cannot agree on how it should be communicated to the public?

In the discourse of honesty, the opportunities for architectural experiences may reside with the smallest common denominators of life, the everyday moments that one can only appreciate by being mindful of the surroundings, the movement of air, the sun and living beings. If the public ever needs to be educated about architecture, it may not be necessarily about the significance of certain architects or buildings but rather the beauty of materials, thoughts and labour of love behind our built environment and the ways of appreciating the simplest details that spark joy depending on how one interprets. It may be how one can ‘feel’ the breath of architecture – tangible and intangible characteristics of the environment – and form one’s perspective on spatial experiences.

As Takubo felt the genuine beauty and purity of those wall paintings at La Grottes de Lascaux, knowing what to observe and appreciate (in his case, he could read into simple yet timeless painting techniques in depicting dynamic movements of animals) can invite people to experience eye-opening moments, shaping how one relates to the world.

Perhaps dishonesty in architecture is the depiction that it is out of reach for the general public, expensive, and reserved for the privileged. Honest and genuine architecture may only be possible when there is a mutual understanding that it is multifaceted, takes time to emerge, and is everywhere around us.

Reference:

Francis-Jones, Richard. 2022. Truth and Lies in Architecture. First edition. Novato, California: ORO Editions.

Takubo Kyoji. 1998. 林檎の礼拝堂 La chapelle des pommiers. Tokyo: Shueisha.

Cover photo credit: Falaise Suisse Normande