The book on Japanese architecture (日本の建築, ‘Architecture of Japan’, published in November 2023) by Kongo Kuma explores how Japanese architecture has been defined and juxtaposed against the cultural, social and political climate of a particular point in history. Calling it a ‘mirror’ that continues to reflect our everyday life in Japan and how Japanese architects of the past grasped it, Kuma unravels the multiplicity and diversity of Japanese architecture, which were cyclically abandoned to form a single, continuous and sacred “dead” identity – the history of architecture in Japan is a series of denial of alternative conceptual approaches that do not fit in the (perceived) established mainstream narrative of the time.

Unlike any other book on the history of Japanese architecture, this book treats Japanese architecture as a lens into the history of tensions – between ‘Yayoi’ and ‘Jomon’ characteristics, the imperial and feudal traditions, the Eastern and Western Japanese traditions, the European and ‘Japanese’ in the Meiji period, and concrete and timber. Recognising the identity of Japanese architecture as a fluid medium enables the reader to accept that Japaneseness has very much been discovered through exposure to external influences – from neighbouring Asian countries, Europe and the United States in particular, both by Japanese people (including those who studied overseas) and people of non-Japanese heritage.

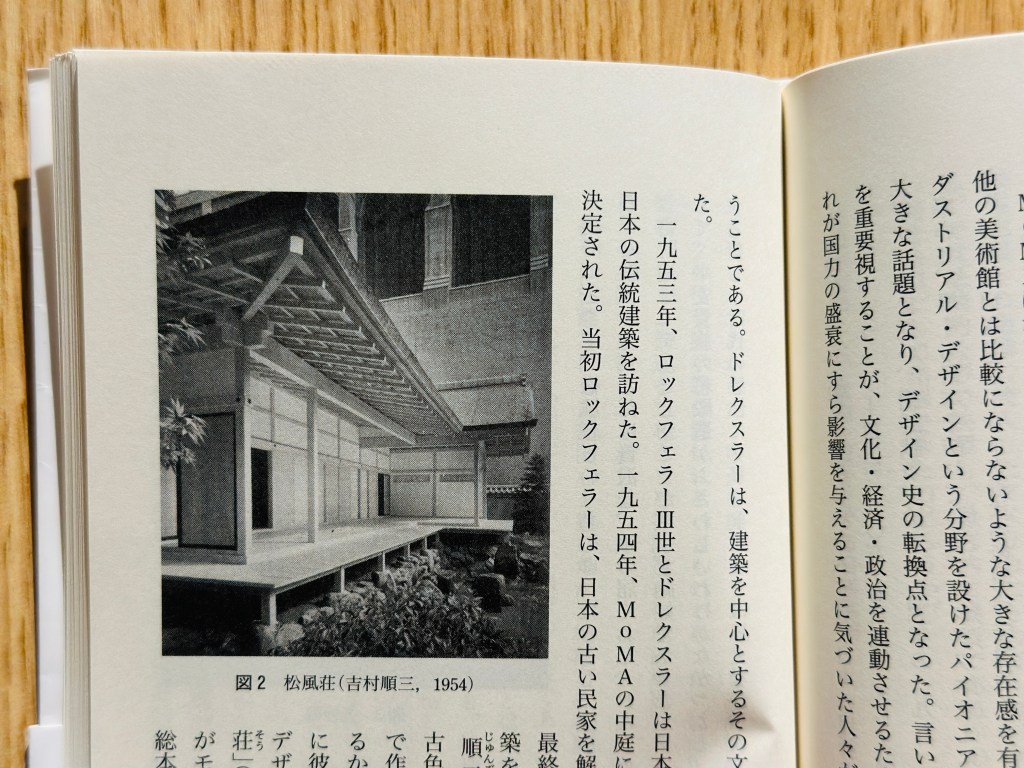

Another aspect of the society that Japanese architecture as a mirror portrays is the recurring, often top-down, unquestioned deference to Western/European influences. The embrace of the cultural and industrial revolution in the Meiji period and Modernism in the 20th century instead highlights the duality of perception of ‘Japanese architecture’ in Japanese society. While society has often been perceiving the complex architectural tradition as an old relic of the historical past in light of the new foreign inspirations, the international recognition of ‘Japanese architecture’, the very thing the society tried to disregard, instead yields a sense of pride in the society. The story in the book about the construction of Shofuso by Junzo Yoshimura at MoMA is an example of how the carefully curated purity of Japaneseness (almost treated like a brand identity of a packaged product) appeals to the international audience and how those people’s appreciation of such Japaneseness then gets fed back to Japanese society, reinforcing what Japaneseness is supposed to be. This vicious cycle further prevents us from recognising and embracing diversity within Japanese architecture.

One of the most fascinating parts of the book is the chapter on six so-called ‘eclectic’ architects (Koji Fujii, Sutemi Horiguchi, Isoya Yoshida, Togo Murano, Antonin Raymond, and Charlotte Perriand), four of whom had Japanese heritage and travelled and experienced prerevolutionary Europe before the wake of Modernism. In particular, Koji Fujii and Sutemi Horiguchi fought for the continuation of architecture embedded in Japan in the period where the obsession with Modernist, industrialised aesthetics with a sense of freedom reinforced the negative perception of Japanese architecture.

Both Koji Fujii and Sutemi Horiguchi criticised the very nature of Modernist architecture: being devoid of site (environmental, cultural and material) specificity. Fujii explored engineering and tectonic approaches in nurturing the relationship between the place and his modest architecture. For instance, in Chochikukyo (1928), Fujii integrated the cooling tube system to demonstrate the importance of airflow in a hot and humid Japanese climate. Furthermore, in contrast to Le Corbusier’s free facade concept enabled by large-scale structural elements away from the building perimeter, Fujii’s use of fine-grained timber structure not only achieved freedom of facade composition but also made the structural elements disappear; elements such as timber shelves, sliding partitions such as fusuma and shoji and earthen walls bore thoughtfully integrated functionality and load bearing attributes, demonstrating Fujii’s ability to outshine the quality of transparency and flexibility that Modernists claimed while ensuring architectural connection to the place.

Similarly, Sutemi Horiguchi, known for the studies of tea houses encompassing architecture, landscape(garden) and all the elements that create its spatial experience, focused on the materiality of Japanese architecture. Criticising the industrialised Modernist housing detached from urban spaces, Horiguchi argued natural materials create a sense of peace and harmony with nature through their impermanent, tactile qualities. His understanding of Japanese architecture articulated the significance of place as an assembly of local materials in various forms and relationships.

Kuma employs the adjective ‘yowai’ (sensitive, weak) extensively in describing the Japanese architecture Fujii and Horiguchi explored. Perishability, sensitivity, impermanence, modesty, responsiveness – these ‘weak’ aspects resonate with the philosophical underpinnings underlying the multitude of ‘Japanese architecture’ that continues to transform like a living creature.